One conventional measure of ‘success’ in smoking cessation is the proportion of smokers who, when then have used the X method, are not smoking one year later. For example, many studies show that of smokers who quit using medicinal nicotine (gum or patches), around 16 per cent are still not smoking a year later. Not very impressive but this is a statistic that is often quoted to support the claim that nicotine gum or patches is significantly superior (in a statistical sense) to stopping smoking abruptly. (There is, however, one very interesting study which shows that stopping abruptly has a much higher success rate than using nicotine products.)

One conventional measure of ‘success’ in smoking cessation is the proportion of smokers who, when then have used the X method, are not smoking one year later. For example, many studies show that of smokers who quit using medicinal nicotine (gum or patches), around 16 per cent are still not smoking a year later. Not very impressive but this is a statistic that is often quoted to support the claim that nicotine gum or patches is significantly superior (in a statistical sense) to stopping smoking abruptly. (There is, however, one very interesting study which shows that stopping abruptly has a much higher success rate than using nicotine products.)

But suppose someone starts smoking again after a year and a day?

I’ve had experience of this with a few of my patients. They stopped with the help of my method, apparently successfully, but then started again after two or three years.

I’ll describe in a little more detail one patient to illustrate the problem. She stopped for two years but when someone at a party offered her a cigarette she impulsively accepted and smoked it.

Predictably, two things happened. First, she didn’t enjoy smoking that cigarette and wished she hadn’t. Second, the previous addiction to nicotine was triggered by the dose of this poison in just that one cigarette. As a result, she immediately was back on the fifteen cigarettes per day which she had smoked previously. She came to see me for another session to be reminded of my method and was then going to stop for good. But she didn’t want to stop straightaway. Why was that? Because she was in the middle of some personal problems and planned to stop when hoped these would have been sorted out a few months later.

This situation isn’t uncommon. Conventional smoking cessation counsellors might well say of this person: ‘She didn’t fail, she just needs to keep trying!’ I suppose this is meant to be kind since using the word ‘failure’ suggests a measure of censure. But a smoker could be defined as someone who’s failed to quit: this is demonstrated every time they light another cigarette.

More to the point, it illustrates the tragedy of smoking. Because in an unguarded moment the above patient reverted to her old, mistaken way of thinking about smoking (if she thought at all) as something enjoyable or helpful in coping with stress, she relapsed to smoking again. Yet she would have been counted a success if her initial period of abstinence had been assessed by conventional means.

The tragedy of smoking is also shown with another smoker patient whom I saw regularly over a few years for unrelated problems. He wanted to quit, was well aware of all the reasons for quitting and the dangers of not doing so, but he told me that the thought of never smoking again was intolerable. He knew this was illogical and he didn’t even enjoy smoking. Clearly, this was a psychological problemt—but it had a powerful effect.

I suspect many smokers are in this situation and this is why the results of conventional treatment with nicotine products, drugs, etc., are so poor. As mentioned above, the success rate at best is only 16 per cent. This is because smoking is regarded largely a physical disorder and the implication is that if only you can get over the anticipated awful withdrawal symptoms you will in theory never want to smoke again. Such an approach overlooks the fact that smoking is a psychological problem.

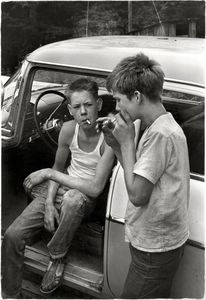

As long as cigarettes are on open sale there will always be a conflict. On one side there is the lure of the imaginary pleasures or benefits of smoking, and against this we have official discouragement to smoke with health warnings, horrible pictures, high prices through taxation (at least in some countries), smoke-free public places, etc.

Is it not unacceptable that smokers, to say nothing of impressionable young people who may be drawn to smoking through wishing to imitate adult behaviour, are put in this dilemma? Whichever way you look at it, it’s absurd—not to say outrageous—that tobacco products are allowed to be sold at all.

Before my critics rush to attack me as an agent of the nanny state who’s trying to interfere with smokers’ legitimate rights to enjoy smoking cigarettes if they so choose, allow me to remind them of the reality: smoking is legalized drug addiction that worldwide kills seven million people every year.

Text © Gabriel Symonds

Leave A Comment